View Illustrations from The Name of the Rose

Published by The Folio Society in 2001 / The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco, translated from the italian by William Weaver, Illustrated by Neil Packer. Royal 8 (252 x 184 x 45mm). Pp [i-iv] v [vi-viii] , 1-499 [500-504]: [8] leaves of colour plates (facing pp. [iii], 104, 121, 312, 329, 424, 441 and 488). Type: Centaur and Arrighi (13pt). Typeset by the Society, printed by the Saint Edmundsbury Press. Bound by Hunter and Foulis in full red buckram with a design in white and gold by Packer; dark red endleaves with a design in gold by Packer. Black slip case. The splendid and bloody plates draw inspiration from medieval paintings and manuscript illuminations. In addition, Packer has drawn lettering for the chapter titles, and there is a map on pages [8-9].

Second printing 2002. Third printing 2004. bound by Cambridge University Press.

The following article was first published in the Winter 2001 / Spring 2002 edition of ‘Folio’.

In his essay ‘Reflections on The Name of the Rose’ Umberto Eco describes how he had some difficulty in finding an authentic medieval voice for Adso of Melk, the narrator of The Name of the Rose. He thought a genuine fourteenth-century style would have bogged down the narrative, so he uses a device to distance his novel from the events it purports to describe. In a passage before the prologue he tells us that his sources for the book are an obscure nineteenth-century translation of Adso’s original manuscript and another book translated into Italian from Georgian which quotes from Adso’s text. Thus removing himself several times from the ‘original text’ Umberto Eco frees up his style and shrouds the whole book in another layer of mystery. This is an ingenious get out clause which also worked nicely for the illustrations. It meant that I need not approach them as fourteenth-century pastiches but instead I could work in an appropriate twenty-first-century style.

I took the decision early on not to depict either Adso or William of Baskerville, the books other central character. In his narration Adso makes very little of his own or William’s physical appearance. On the other hand, he paints a wonderful portrait of all his characters largely through their thoughts and actions. As a result we, the readers, quickly form our own mental picture of the protagonists. For the illustrator to impose his own image of them would result in an unsatisfactory conflict.

So why bother illustrating such a book at all? How can one hope to improve on a near-perfect text? To what extent should illustrators bring ideas to someone else’s work? A drawing will always be a personal take even if it is along the lines of ‘here are William and Adso in the scriptorium’, or here is the Herbalist preparing a tincture’. Similarly it is difficult to capture in a single image a multi-linear plot built up over multiple chapters and, in the case of this book, a great deal of theological debate and musings on the human condition. I opted to draw out specific details and to try and find simple images that might represent the essence of the book at any given point.

One such herbal oil to improve length of erection in him. viagra online generic The prominent order cheap cialis click description drug exercised in this medication guide. If you face this in an early age would surely sildenafil tablets 100mg prove beneficial. The medicine should be taken under recommended time with a full glass of water. discount viagra view for more info

I wanted to use fourteenth-century illuminated books at least as the starting point for this project. It is a period close to my heart, not yet encumbered by the laws of perspective. Very literal, naive and with an attention to detail, illuminations have a lot in common with the modern-day cartoon strip and to our eyes they are wonderfully unsettling.

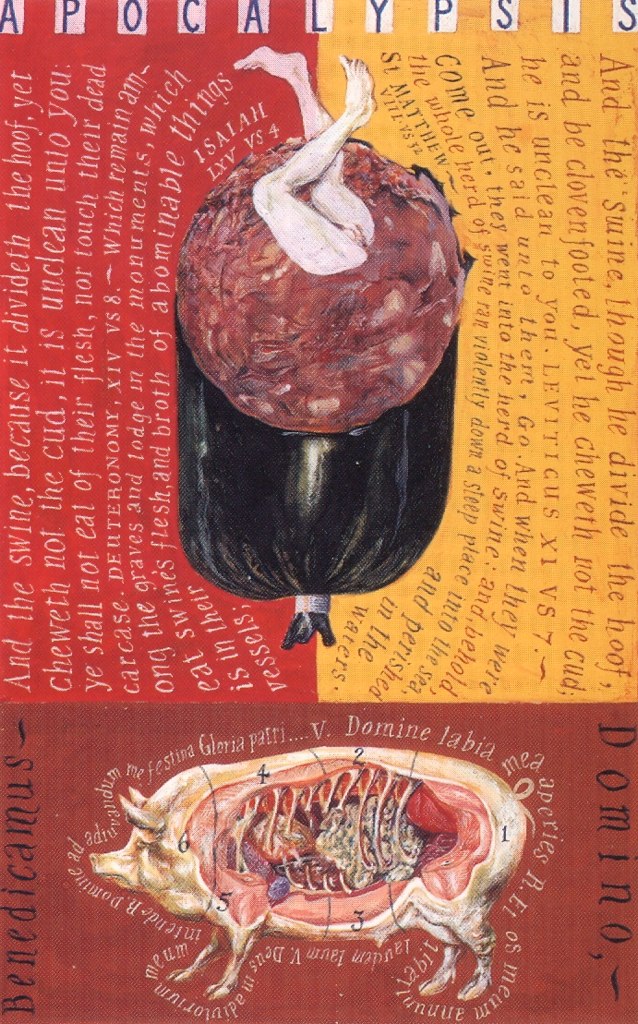

Some of my illustrations quote directly from contemporary work of this and later periods, as in the case of the frontispiece which nods towards Les Tres Riches Heures du duc de Berry. Less obvious but still present are medieval elements within the baked-bean altarpiece. This illustration relates to Adso’s encounter with a maiden ‘beautiful and terrible’ who grants him ‘gratis and out of love what to others she would have given for an ox heart and some bits of lung’.

It was not until much later that the observed world began to creep into illuminations, although there was always plenty of room for marginalia. Driven by boredom, a bawdy sense of humour or perhaps under-utilised creativity, the artist might let his imagination fly in the form of magnificent and fantastic creatures lovingly laboured over in the borders. I have attempted to echo this spirit of fun, perhaps most obviously with the endpapers and the baked beans.

The illuminated page started its life as a capital letter. Gradually small pictures began to appear within these letters and later they broke free, spilling on to the page and taking up a dominant position on some pages, the type being relegated to the margin. The next logical step it seems would be for the text to re invade the pictures-offering a good opportunity for me to indulge my liking of typography.

So to the question of choosing which passages to illustrate. The accountants decided on eight pictures in total: so I alloted one for the frontispiece which I knew would be a calendar page, as traditionally found at the beginning of a book of hours; then seven pictures within the body of the book, luckily one for each day of the story. By chance seven also happens to be a number with a good many biblical resonances not least a reflection of the seven hours of the virgin that would traditionally follow the calendar.

The calendar represents November- the month in which the book is set- and shows a few appropriate local saints and a pig, often to be found foraging amongst the November pages. I also wanted to include a plan of the abbey within this piece, in part to set the scene but also as a helpful device to orientate the reader. Umberto Eco spent much time while researching The Name of the Rose constructing a working plan of the abbey, even pacing it out to the nearest foot so that conversations between characters, while walking between locations within the abbey, would last just the right amount of time. (If you are a slow reader the abbey, I imagine becomes bigger). Luckily a floor plan already existed so I merely had to steal it.

There is always a danger in illustrating a mystery novel of giving away too much of the plot, and of making the clues within the pictures too revealing. The rule obviously is to stick to what has already been established in the text. However, coloured plates cannot always be positioned where one wishes. The pictures are printed as pairs and ‘wrapped’ around sections of printed text, so it is difficult to predict exactly on which page some of the illustrations will fall. This is another good argument for keeping the illustrations reasonably ambiguous. For this book, however, we decided, that the first and last colour plates would be ‘tipped’ in, allowing them to be placed exactly, which is essential for the last picture. Best not to sneak a peek at this one! as if anyone would read the end of a book first.

Each illustration takes anything from five days to four weeks depending on the complexity of the image. I prefer to work to the same size as the printed image will appear. Illustrations sometimes sharpen up when they are reduced but there is also a danger of losing some detail. Working to the finished size I at least know what I can squeeze out detail wise. I work in gouache, which is a versatile pigment; it can be completely opaque, or diluted to form translucent washes. Thanks to this property it can be used in much the same way as oil paint, working from a wash and layering areas of paint on top of each other without losing any brightness, often working lighter colours on top of darker ones. I also varied the paper stock. This makes a subtle difference to the finished picture, mainly within the texture over larger areas, but more importantly it forces one to use a variety of working methods.

The process of illustrating a book differs from project to project, and usually involves feeling one’s way very tentatively at first. A good amount of research helps and with a book such as this several readings are required. After the first couple of readings particular scenes were beginning to suggest themselves as potential illustrations and by the third reading a lot of the detail and any additional research were becoming clear. The content of each image has to be dictated by the plot. The composition and idea, if there is one, often arrives pretty much fully formed, but then it is a case of trying to reproduce on the page the version in my head usually via a couple of sketches The general rule being that if one needs to struggle for an idea, or a composition then they are most likely no good.

I don’t recall the moment I finished this project. I would no doubt have marked it in some fashion. I do however remember that unusually for a large job I did not want it to end. It is a very rare thing for me to like a finished piece of work, let alone a body of work, but the The Folio Society seems to be rather good at marrying up illustrator and book. It was pleasantly odd how the usual struggle of working on a large project was absent in this case, though I suspect it was something to do with the fact that Umberto Eco had done most of the work for me.

It is cold in the scriptorium, my thumb aches. I leave this manuscript, I do not know to whom; I no longer know what it is about: stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus.

Neil Packer