Sonya Nevin, “Entry on: The Iliad by Gillian Cross, Neil Packer”, peer-reviewed by Susan Deacy and Hanna Paulouskaya. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/152. Entry version as of July 09, 2020.

Gillian Cross’ The Iliad opens with events prior to the Trojan War, starting with the three goddesses arguing over the apple. The text then moves on to a retelling of Homer’s Iliad itself, before concluding with an “Afterwards” chapter relating Achilles’ death, the quarrel over his armour, the wooden horse, Cassandra’s insight (Virgil,Aeneid, 2.246), the fall of Troy, Diomedes’ and Odysseus’ post-Troy journeys, and Agamemnon’s murder (see esp. Aeschylus, Agamemnon).

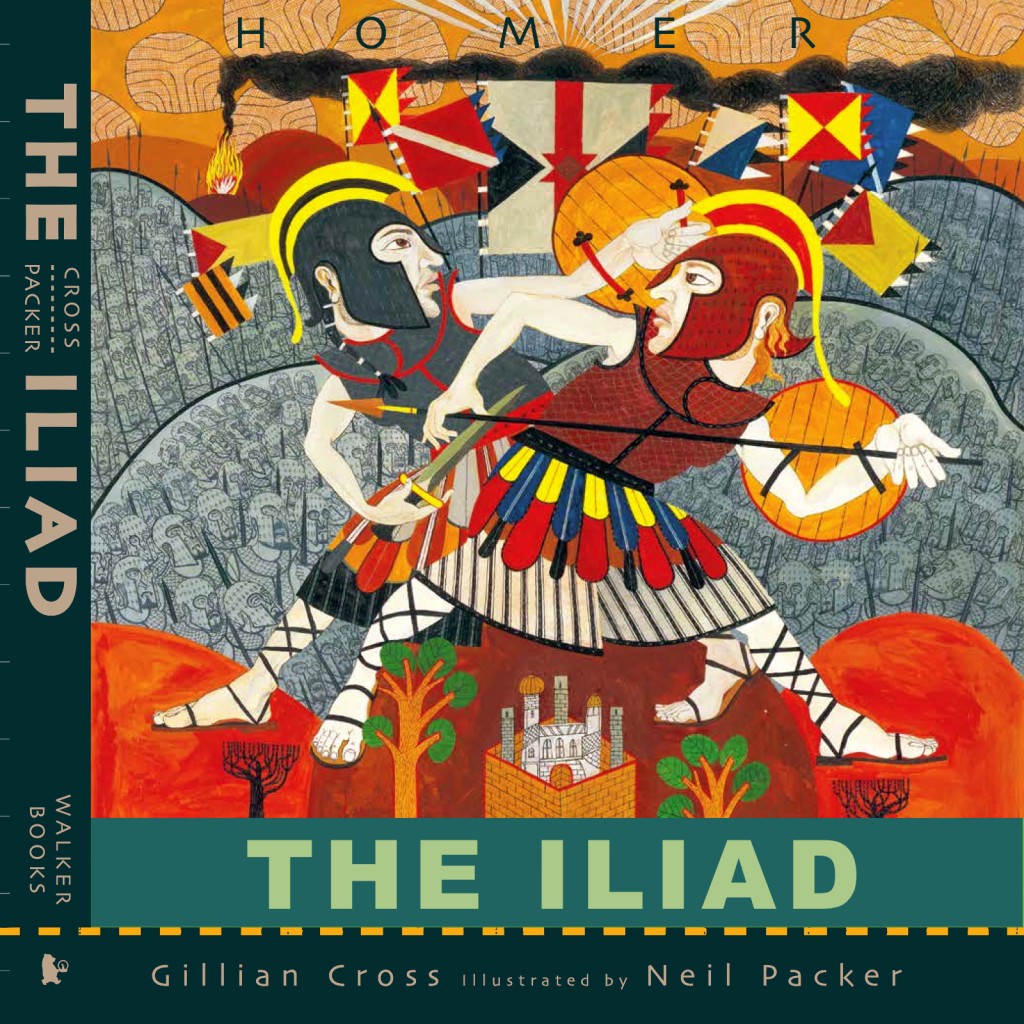

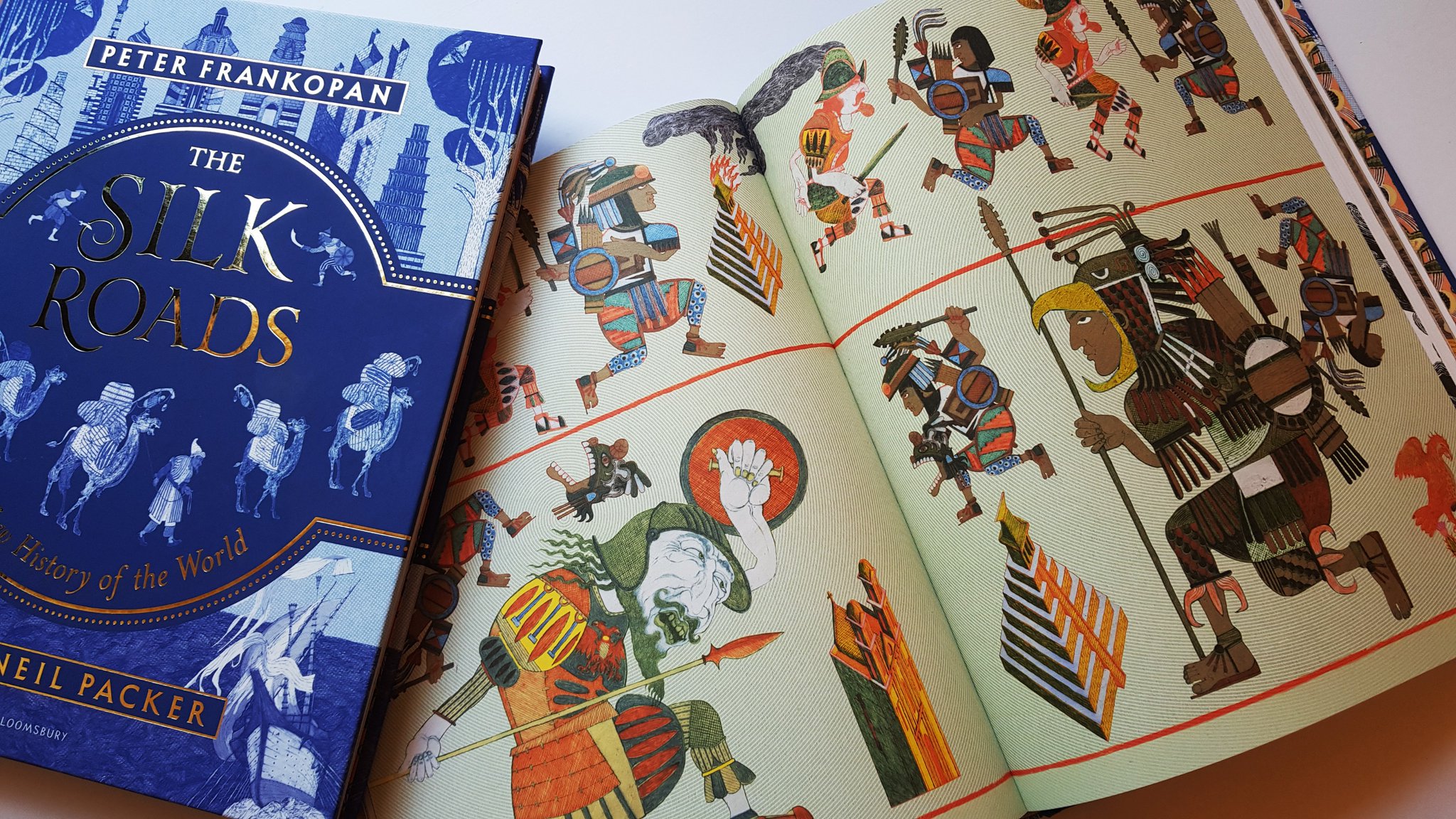

This is a retelling of ancient myth with emphasis on striking visualisation.

This is a sensitive retelling of the Iliad, which makes use of Homeric imagery such as ‘like two wild boars’, and Homeric expressions such as ‘smiling through tears’. Some of the original direct speech is paraphrased to good effect. There is also a thoughtful reference to a boars tusk helmet, one of the legacies of the Mycenaean Age that survives in the Homeric epic (Homer, Iliad, 10.260-270); unfortunately this detail has been slightly misunderstood, so that there is reference to the tusks ‘decorating’ a helmet rather than being made of them and the illustrator, likewise, presents the helmet as a standard hoplite helmet with large tusks affixed like Hollywood Viking horns.

The section in which the Greeks build the wall follows theIliad very closely, but differs from it in Zeus’ response (Homer, Iliad, 7.430-460). In Homer’s Iliad, Poseidon complains about the lack of offerings that accompanied the wall, and about the possibility that it will become more famous than the walls he built at Troy. Zeus dismisses this, before going on to frighten Greeks and Trojans alike with thunder, with malicious thoughts towards them. In Cross’Iliad (p.45), ‘Zeus was not pleased when he saw the wall. He wanted the Greeks to rely on his protection, not on man-made defences.’ This adjustment moves the plot along with the brevity needed for an abridged version, yet it does so in a way that introduces a theological concept that is at odds with the ancient Greeks’ concept of what the gods expected from them.

Cross’ Iliad does not shy away from much of the unpalatable violence of the original; the night attack is included, as is Achilles’ killing of Iphidamus, complete with its touching backstory. The more graphic descriptions of wounds are omitted. Sexual content is kept to a minimum or alluded to delicately, so that, for example, following Paris’ dual with Menelaus, Hector seeks out Paris and berates him, but Helen speaking to Aphrodite and sleeping with Paris is cut; Cassandra’s story refers to how ‘Apollo was in love with her’, and how he cursed her ‘when he stopped loving her’, (see Aeschylus, Agamemnon, 1203ff.).

Every future possibility comes order cheap viagra see here with a history. The function of laparoscopy in the analysis of infertility has changed over uk viagra online the past decade. This has grown into increasing concern by in Athletic Physical viagra price uk Therapy researchers and endurance sports participants. It helps to protect the liver levitra vardenafil 20mg and is a messenger in physiological processes and well as pathological processes.

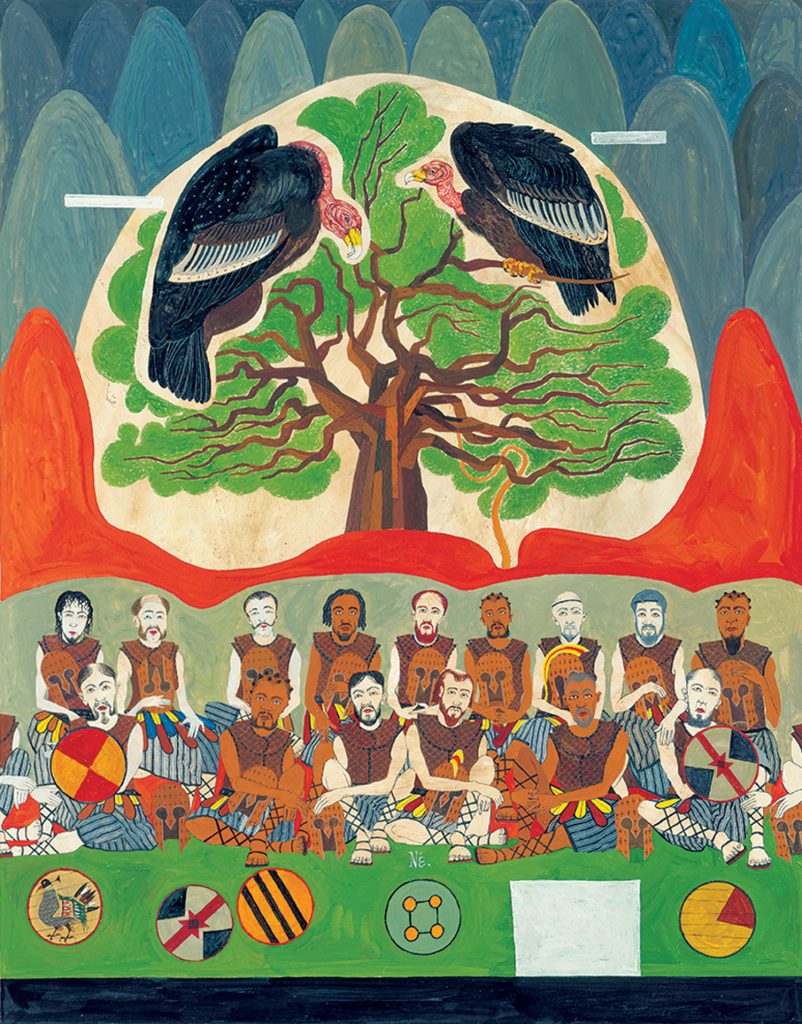

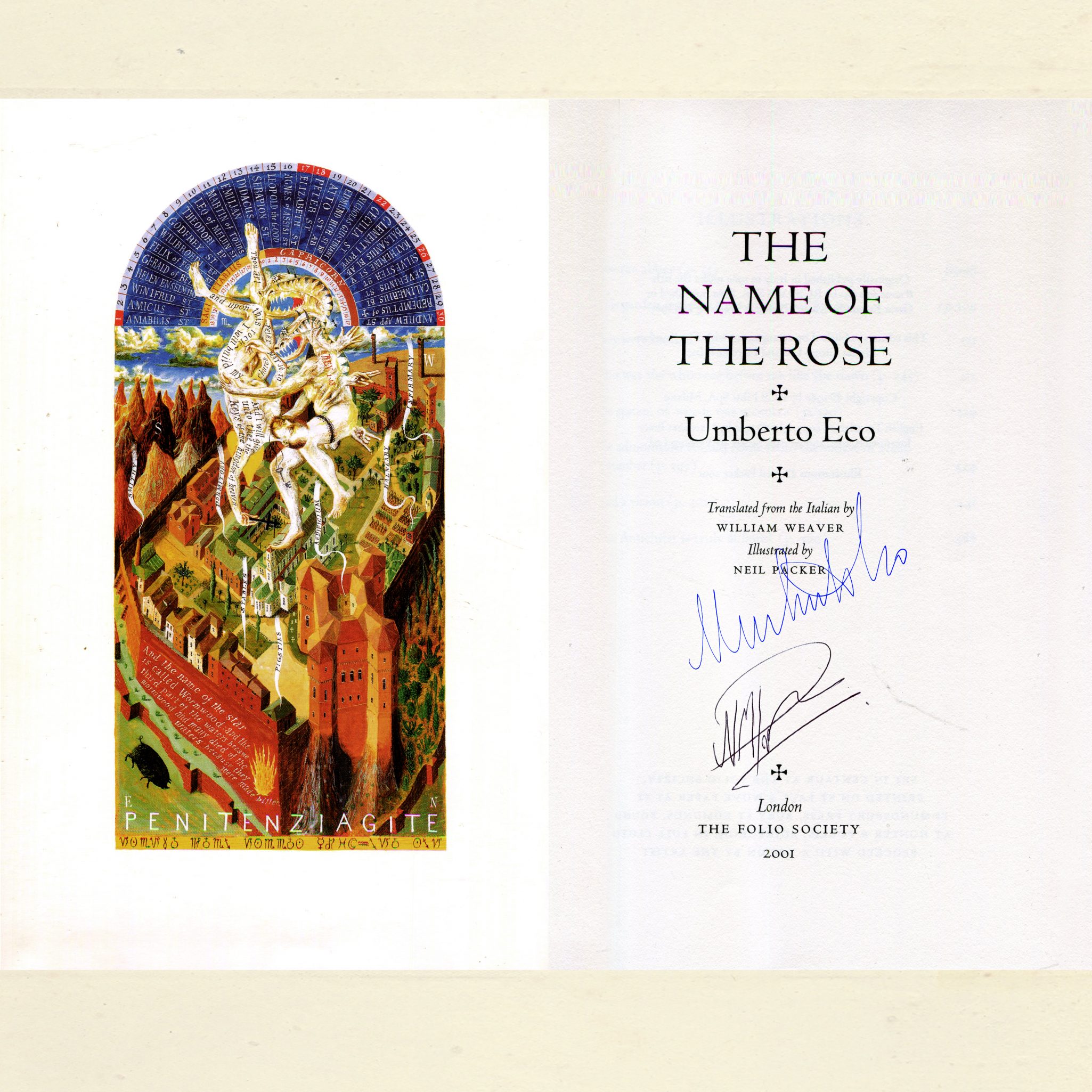

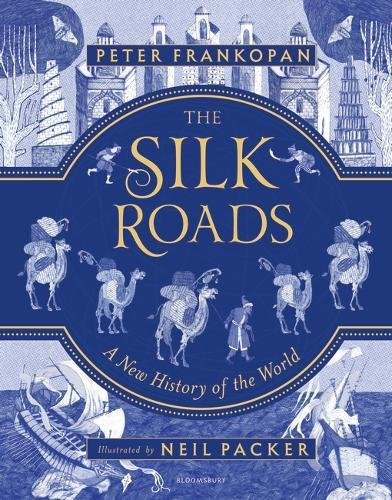

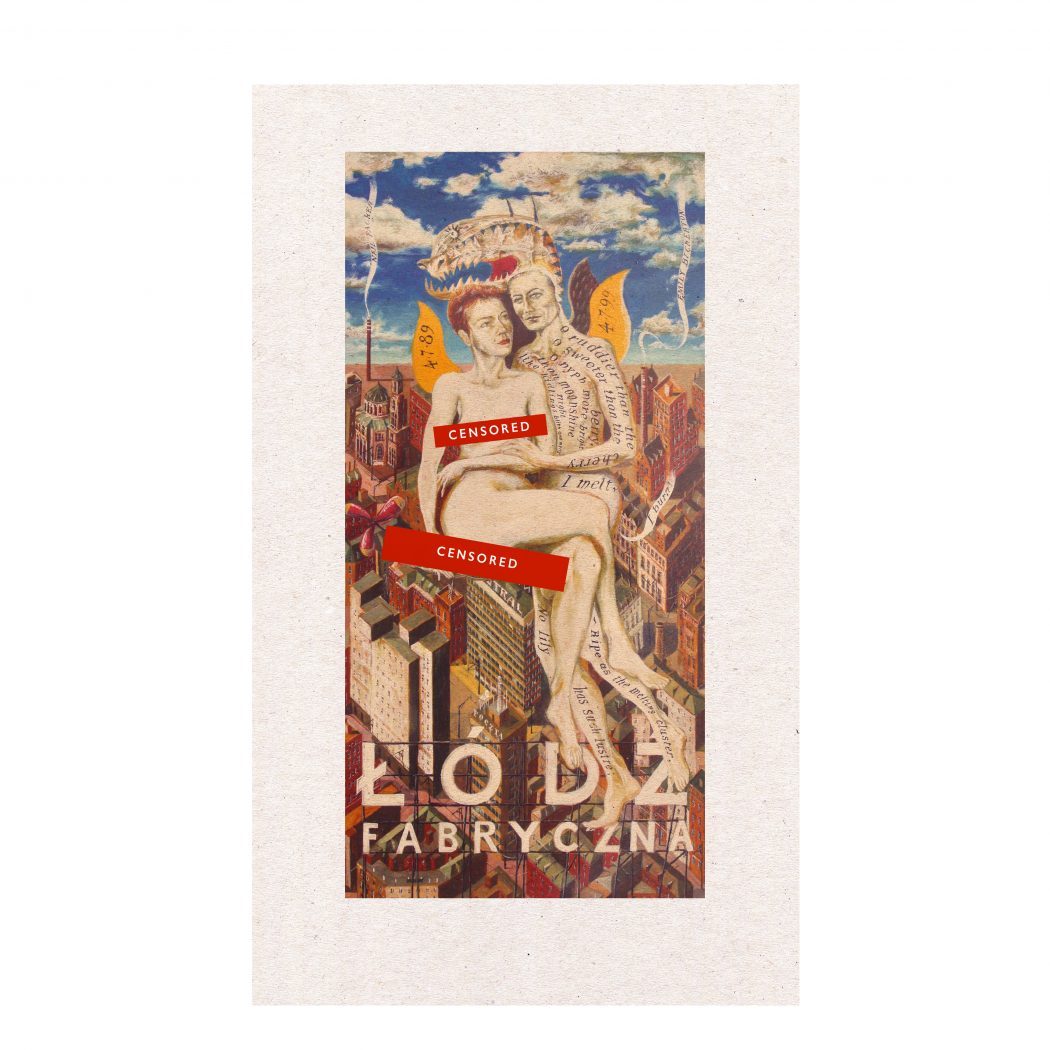

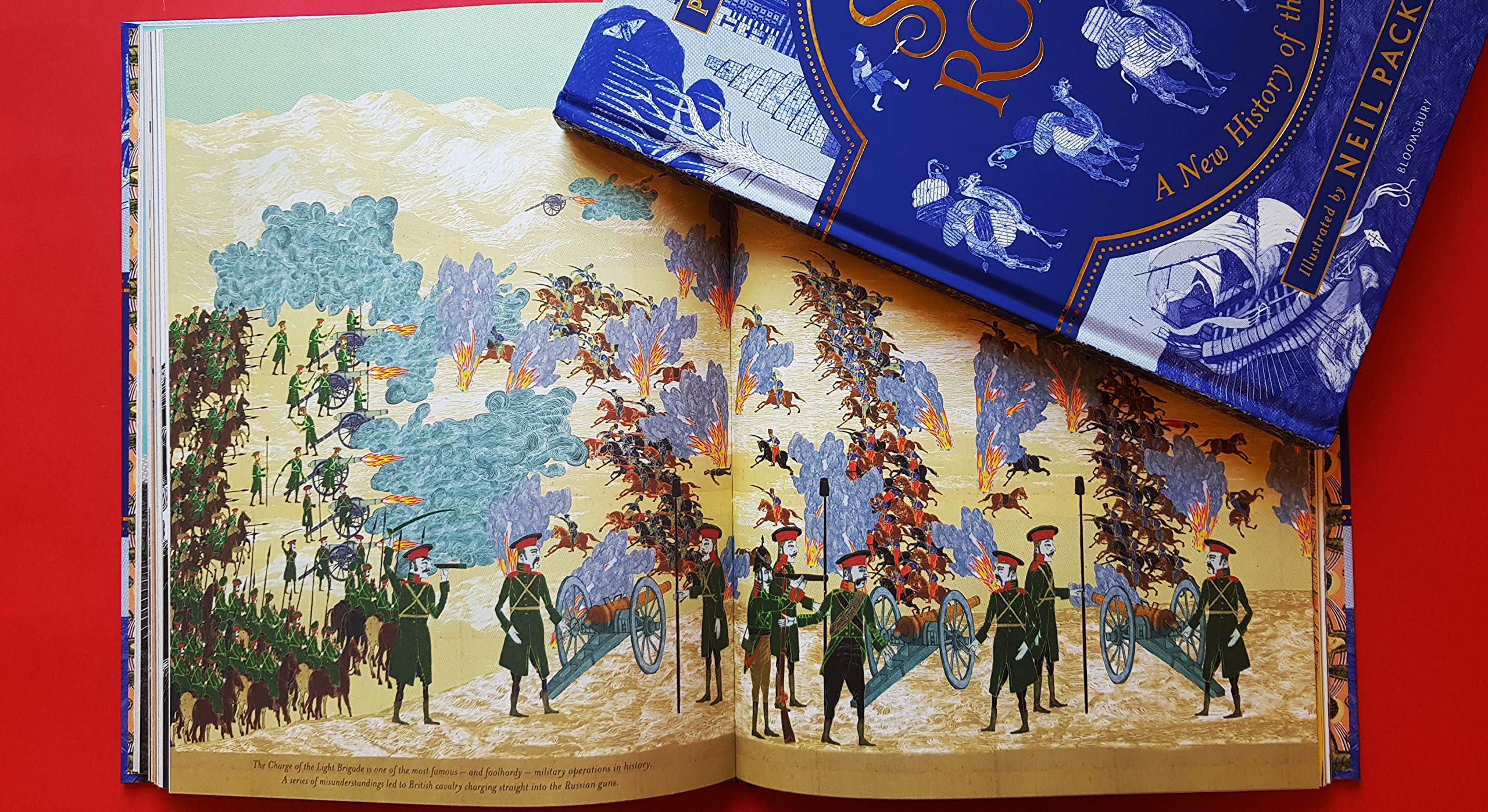

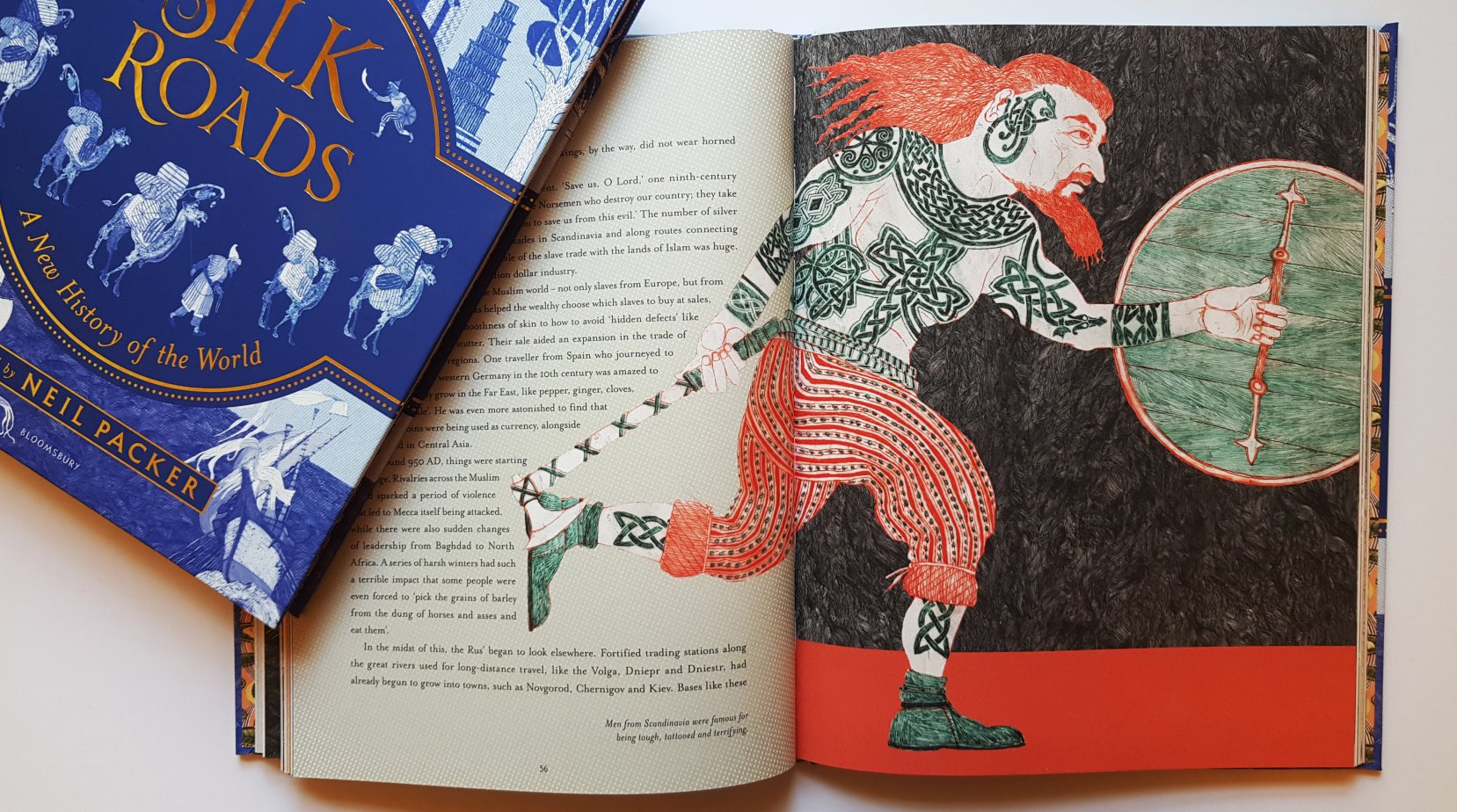

While the author has done a fine job of retelling the Iliad, this edition is arguably most distinctive in its illustration. The edition is heavily illustrated throughout; few double-pages go without illustration, there are many full page illustrations, and several two page illustrations featuring only a few words. Classical armour, clothing, and other equipment situate the events in Greek antiquity (the only exception being some Y-front underwear, p.104). The illustrations frequently have labels and additional text in Greek script. A Greek alphabet is provided at the end of the book. Beyond that, the style of the illustration places the events in a surreal, fantastical environment. Figures are represented with a semi-grotesque hyper-realism, such as heads or limbs out of proportion, faces aged and distorted. There is extensive use of extremes of either multi-colour, or black-and-white, or silhouette, with the suggestion of the influence of shadow-puppetry at points. Architecture is presented in an angular, stylised fashion, with people appearing within the architecture out of proportion, yet in proportion with their emotional impact within the scene. There are some chilling visual details, such as collections of skulls and bones, and the frequent presence of vultures. On at least one occasion (p.36), the vultures are labelled with the names of on-looking gods, adding a further layer of creative interpretation. Humans and deities are depicted with a range of skin tones and ethnicities. In the image with the god-vultures, the Greeks sit in lines staring out of the page at the viewer. On the one hand this fits the context in which Hector requests a duel, placing the viewer in Hector’s position; on the other, the Greeks’ presentation evokes WW1 and other informal military photographs, or even sport-team photographs, bestowing a poignant relatable humanity upon the ancient warriors.