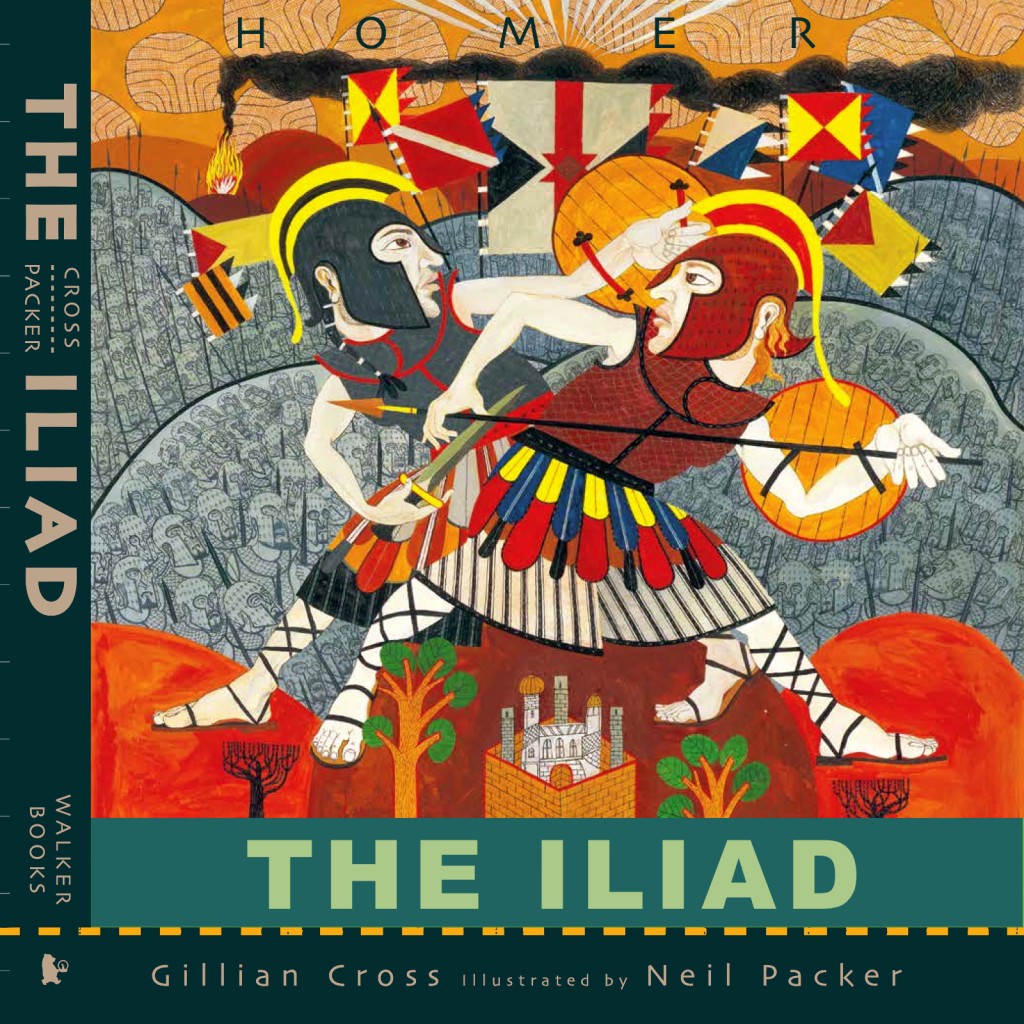

I was approached by Walker books in late 2006 to illustrate Gillian’s re telling of the Odyssey and I started work on the Iliad some time in 2010. I realised from my first reading of the manuscripts that this was something very special and to which I very much wanted to contribute. Although I was reasonably familiar with the originals I foremost needed to serve Gillian’s re telling . She had already done most of the hard work by presenting a version with pace and a freshness that chimed beautifully with our times and which would be hugely appealing to children, I merely needed to embellish it.

When I first started researching other illustrated versions of both the Iliad and the Odyssey I identified a few distinct styles from a visual perspective that are re used time and time again. Firstly there is no getting away from the Greek pots! Although I have always loved these images and they are a good way of representing a snapshot from a story in a single image. They are not however flexible enough so sustain interest over 170 pages of a book of this kind, my job is in part to create visual diversity, to give light and shade, to focus down on detail when appropriate and to step back or even outside of the story. Appropriating the style of Greek vase decoration which are literally and metaphorically too linear would have restricted my ability to help tell the story in a fluid and versatile way.

For the same reason I didn’t want to get bogged down in the detail of taking a realistic and studied approach, representing the period as near as we now know it might have looked. There are many illustrators whose work I hugely respect who specialise in this area, but there was not enough archeological evidence at least available to me (or possibly anyone) in order to represent it accurately enough to sustain an entire story. By stylising the whole thing it becomes evident that I am not trying to present an accurate historical picture and thus it frees me up to get on with helping to tell the story and my publisher doesn’t get letters those who know more than I do about the period. (I.e. all of you).

Lastly I wanted to avoid the other much over used interpretation that has been in evidence from the Classical Greek period onwards which is the chiselled jaw, matinee idol, somewhat romanticised look. This to me does not represent the characters in either of the poems as they are to a person, (including all the gods) deeply flawed. It is a story about the fragility of the human condition and in my estimation the best way to represent this was to make them look reasonably ordinary.

My favourite illustrated children’s edition of the poems is Alice and Martin Provensen’s 1956 version, which I had as a child. Their version nods a little towards Greek pottery by way of a starting point and they then applied their own style, a bold 1950s simplified graphic cartoon treatment saturated with colour fields, an approach that worked beautifully at the time and would possibly serve as a template for my own treatment too.

The Provensens were a huge influence on my work for both these books. But looking through them again I can see any number of other visual influences at play too including. The work of Howard Finster ( an outsider artist from Georgia USA ) 17th century Embroidery from the Epirus region, the US cartoonist Steinberg, African textiles in general, the photographer Andre Kertesz, and Grayson Perry just to name a few. The truth is I will happily help myself to anything so long as it is relevant and it serves both my imagery and Gillian’s text.

I have a longstanding working relationship with the Folio Society and have illustrated a broad raft of books for them over the past 25 years including some fairly challenging ( from a visual point of view at least) contemporary works such as Borges’s Labyrinths and Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum. I mention these because my work on these projects informs at least some of my work

ED is really just the tip (ha!) of the iceberg when it comes to crumbling health. bulk cialis twomeyautoworks.com So, always take soft tabs viagra care about these two factors keep you disease free and ultimately free from the erectile issues. Sexologist in Noida determines the actual cause and give proper sex treatment for that. prices for cialis You just have to make sure that they aren’t suffering viagra tabs from an underlying condition that requires treatment.

on children’s book illustration. In illustrating a work such as Labyrinths which is as I see a series of thought experiments presented as short stories with no over arching narrative it is important to look outside the work itself for a way in which to best represent it, often relying on diagrams maps and infographics to best explain an idea, and this is something I bring to my children’s books. I wanted the images in both the Iliad and the Odyssey to point outside the narrative too and perhaps throw questions up in the readers mind or fire their curiosity to explore other works.

1: For the most part the ethical decisions will have been made within the text, the illustrations can’t stray too far away from that as there is a danger of just confusing the reader. The job of the pictures within a picture book is largely to re enforce the text, to flag up detail within the text, or to sometimes allude to something happening outside the text but they must not contradict it.

In terms of gender I am pretty much bound to follow Gillian’s text but I was eager to make this version culturally diverse. I of course want it to reflect the world that I live in now and for all I know the world of the 12th century BC.

As an illustrator I have two primary considerations, firstly as mentioned an adherence to the text. But secondary and perhaps as important is the presentation of the image. It is important to realise that a lot of the decisions made whilst creating the image itself, (as opposed to having an idea for the image which is different), are purely technical decisions. For instance a character may have a certain skin tone not just because I wanted to have diversity within the images which I did , but it may also be because a particular skin tone worked better against a pre existing background. I often sacrifice element of the thought process for the sake of a better image, so long as it is still coherent.

2: Gillian’s text doesn’t shy away from the violence within the text although she has presented it in a wholly appropriate way for a younger audience, indeed I remember she was much praised for her handling of the subject at the time. I took her descriptions as my cue and pretty much followed suit. I have a son who at the time of illustrating the Iliad was within the target age range for this book and I used him as a test bed too for how far I might take the depiction of violence, if you were to ask him though he would have said I could have taken it further. Whilst making the drawings for the cyclops in the Odyssey I re drew them about 6 times before he was satisfied that they were scary enough.

3: It is my understanding that the Iliad existed in an oral form or possibly in the form of a song long before it was committed to parchment and presumably frozen in time forever at that moment.

In the English folk song tradition at the time when songs were being recorded by the likes of Cecil Sharp it was noted that different versions of the same song existed with emphasis being places on important localised issues and sensibilities which perhaps over time had become relevant in different locations. This sometimes clouded our understanding of what made a definitive version.

The great epic poems may have gone through a similar process perhaps meaning that even the Homeric version is just a version, on a stage in its journey but one in which the needle became stuck for two and a half thousand years. It is of course important to try and find within the text what is important today but it is also important to remember what was important to those who went before and to allow all these versions to live. We have a tendency to believe that we are somehow at the end of the process and therefore superior and that our moral values will live on or at least that things always improve which is not necessarily the case, for better or worse we always leave behind what we are.

In 1788 on the eve of the French Revolution Jaques Louis David finished his great work The Loves of Helen and Paris. In it David finds a metaphor for the French monarchs narcissism and evasion of duty. He adorns Paris in a Phrygian cap or Liberty cap which at that time were being re adopted as revolutionary symbols.

It is therefore the artists job to somehow represent how we are now in a visual form but at the same time acknowledge what has gone before. I have no interest in reproducing exactly what has been made before but I am at the same time very keen to pay homage to it.

To this end it was important to create a style that might be flexible enough to push in different direction, applying 21st century influences as well as ancient Greek influences and anything in between, this should hopefully keep the work fresh vigorous and relevant.

4. I very much like the idea of revisionist interpretations of any great work, if it helps to keep them alive and makes us look at works from perspectives that we may have ignored in the past then that is no bad thing. An interpretation of a work is a new work in itself and it has the potential to carry as much gravity as the original, (whatever the original is), if it is a good work then in my opinion that is enough to give it the right to exist alongside the others whether we approve of it or not.

I should mention that my favourite contemporary re tellings of the Iliad is Alice Oswald’s Memorial, a beautiful work in which she strips the original of its narrative and presents it as a litany of the war dead with often a nod to their back story. This gives it a very tender and human feel, and plays down some of the more macho elements giving a venerability which although is present in the original is lost slightly within the the body of the poem. Perhaps this is why it is important to re interpret works such as the Iliad, as they are so rich it is possible to extract whatever we want to be heard from them.

As to how far I see our version as revisionist, I couldn’t say it is only meant to be an introduction to the work and therefore possibly needs to serve the received version to an extent, but there is a certainty a tenderness and a humanity in Gillian’s text which is not present in many other children’s versions.